Tackling the foster care crisis

The issue through different lenses

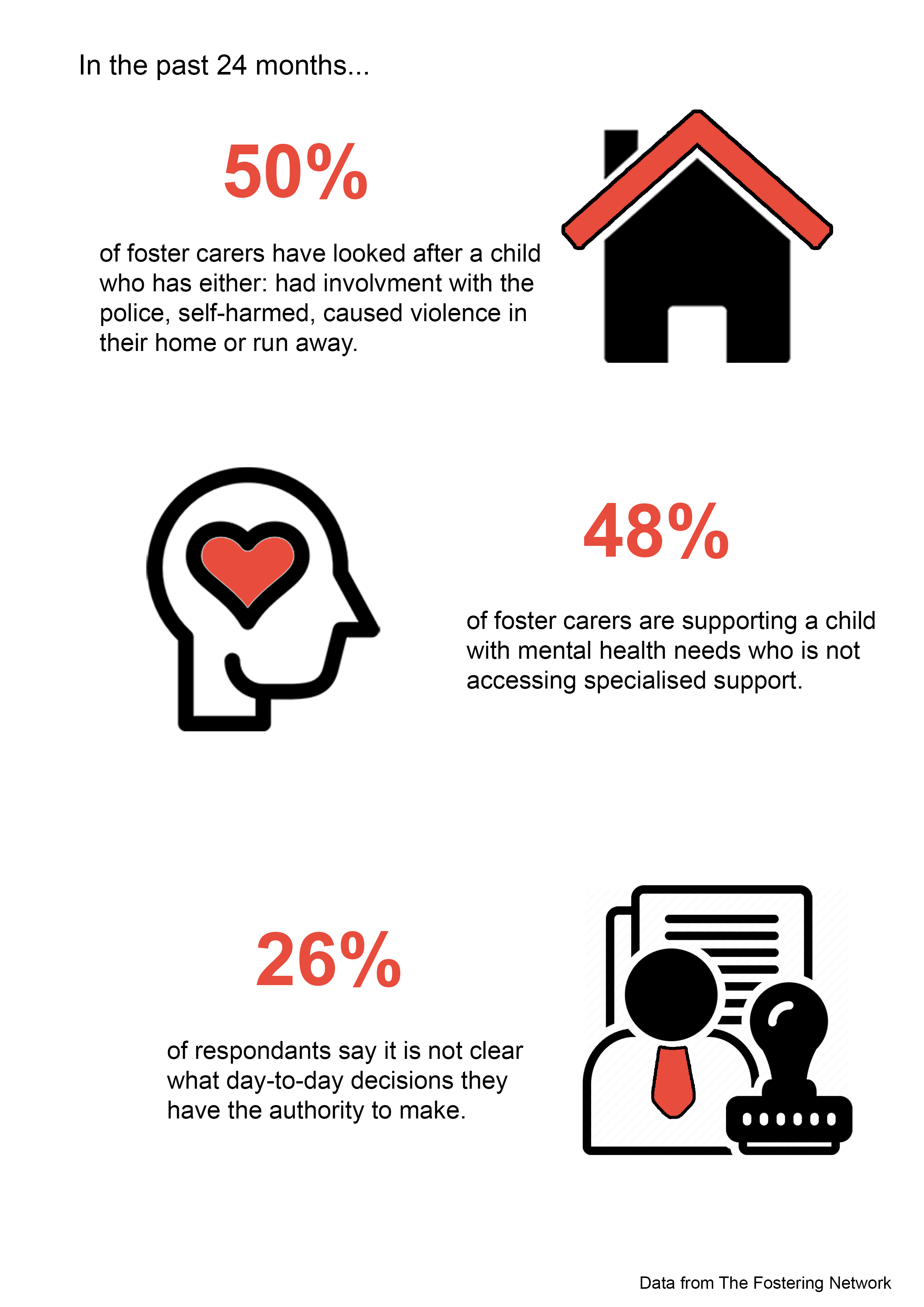

With the number of children neglected and abused skyrocketing in the UK, more than 8,600 extra foster carers are needed this year to meet the demand.

However, the fostering system has faults, leading foster carers to abandon the profession. New fosterers seem discouraged to start the journey.

The increasing number of children who need fostering against the small number of foster carers available created a crisis.

But is there a way to help the vulnerable?

What are foster carers?

Foster carers offer a safe and caring home to young people who are unable to live with their birth family. It’s often the first positive family experience a child has, so it’s important that foster carers are meticulously selected.

Children in an emergency are likely to be put in non-permanent households until they are found with a long-term arrangement or can return home. Others will be looked after for their entire childhood and live in permanent families until they are adopted – often by the foster family itself - or reach adulthood. Some children could be taken into care by friends or relatives.

Why is there a crisis?

According to Ofsted, there are currently 44,450 approved fostering households in England, which includes non-permanent, permanent and family and friends households. However, every year, approximately 8,330 foster carers deregister from the system.

Furthermore, the number of children who need care has risen in the past five years by at least two percent annually.

Under the recruitment targets of The Fostering Network, the UK's leading fostering charity, some fostering services continue to report a lack of foster carers in targeted areas.

They noticed a specific shortage of households who are willing/able to care for teenagers, sibling groups, or disabled children.

There’s now a need to increase the size of the pool of available foster carers in order to improve placement choice.

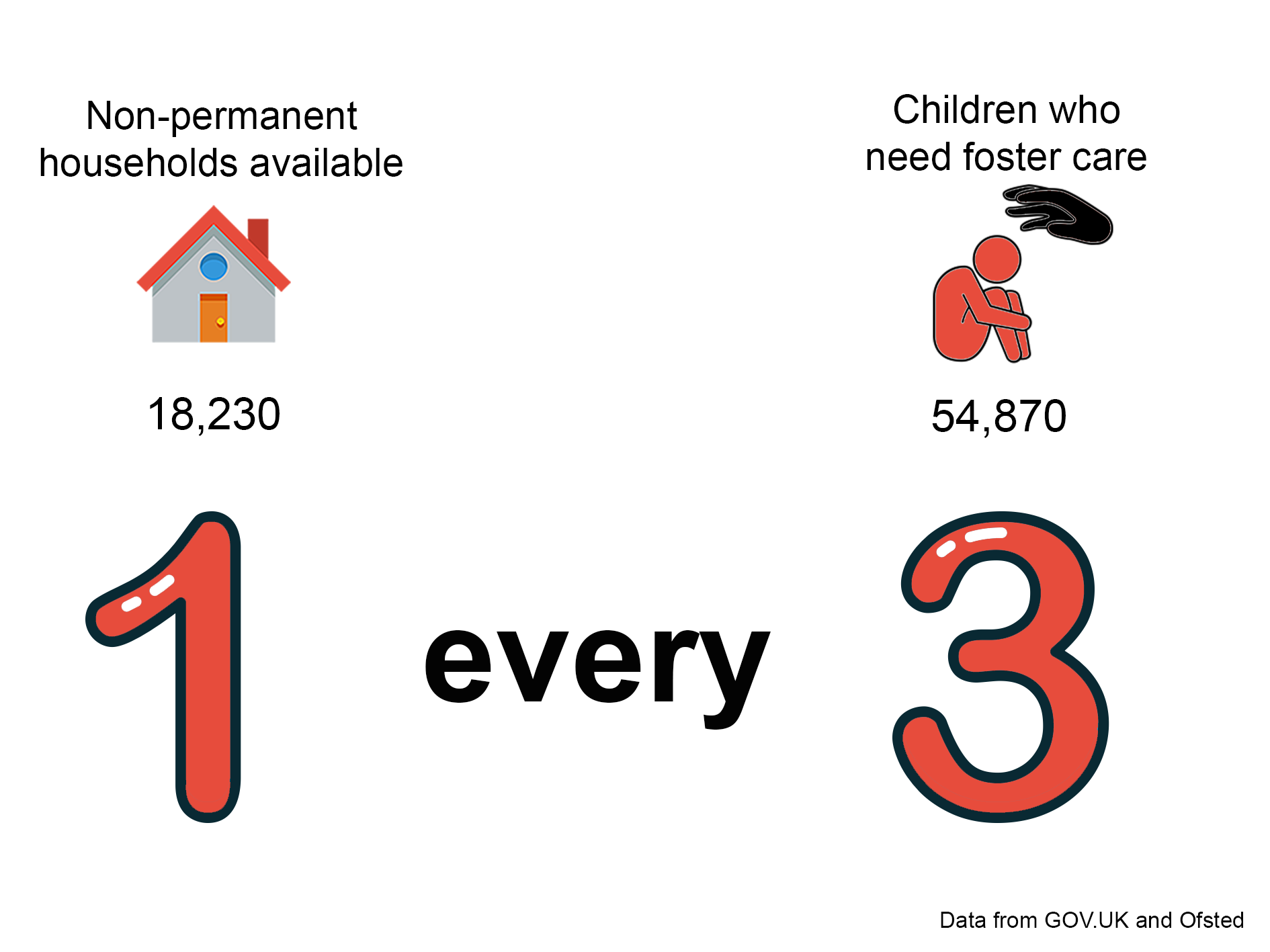

In 2019, almost 55,000 children needed fostering, yet there were only over 18,000 non-permanent households available; that is one household available for every three children who need placement. Non-permanent households are the first port of hold before children are moved to permanent accommodations, return to their birth-family or are adopted.

Currently, there is only one care home for every three children.

Currently, there is only one care home for every three children.

Kevin Williams, chief executive at The Fostering Network, says knowing this ratio is important to understand how many new foster carers have to be recruited.

"Most families will take care of more than one child at the same time, but that is because they have to," he says.

Kevin Williams says there is need of more than 8,600 extra foster carers to meet the demand. Source: The Fostering Network.

Kevin Williams says there is need of more than 8,600 extra foster carers to meet the demand. Source: The Fostering Network.

"This year we need to gather at least 8,600 extra foster families to meet the demand."

Additionally, there is a shortage of foster carers, and of non-permanent households, because temporary accommodations cause stress for the child and the foster carer.

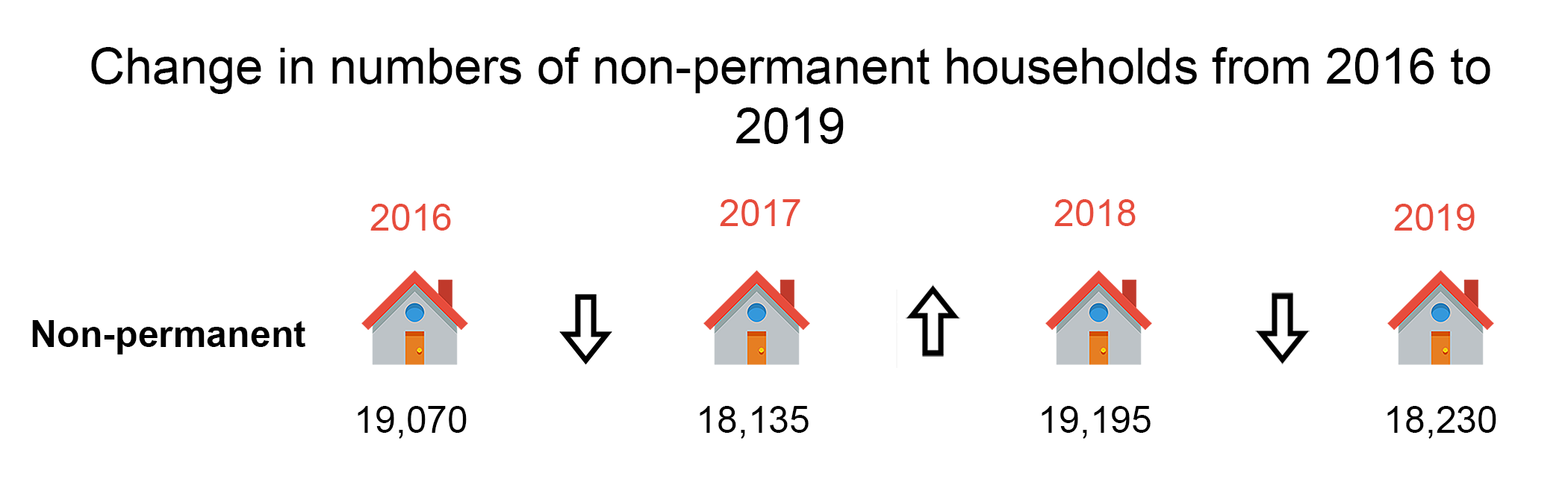

The number of non-permanent households has declined in the past three years. Data from GOV.UK

The number of non-permanent households has declined in the past three years. Data from GOV.UK

"Fostering is known to be short-term, but most of the children who need fostering are actually looking for a permanent family to spend their childhood with," Williams says.

"This means, ideally, most foster carers will look after a single child or siblings, not three or four different children at the same time. But for this reason, we need more workforce."

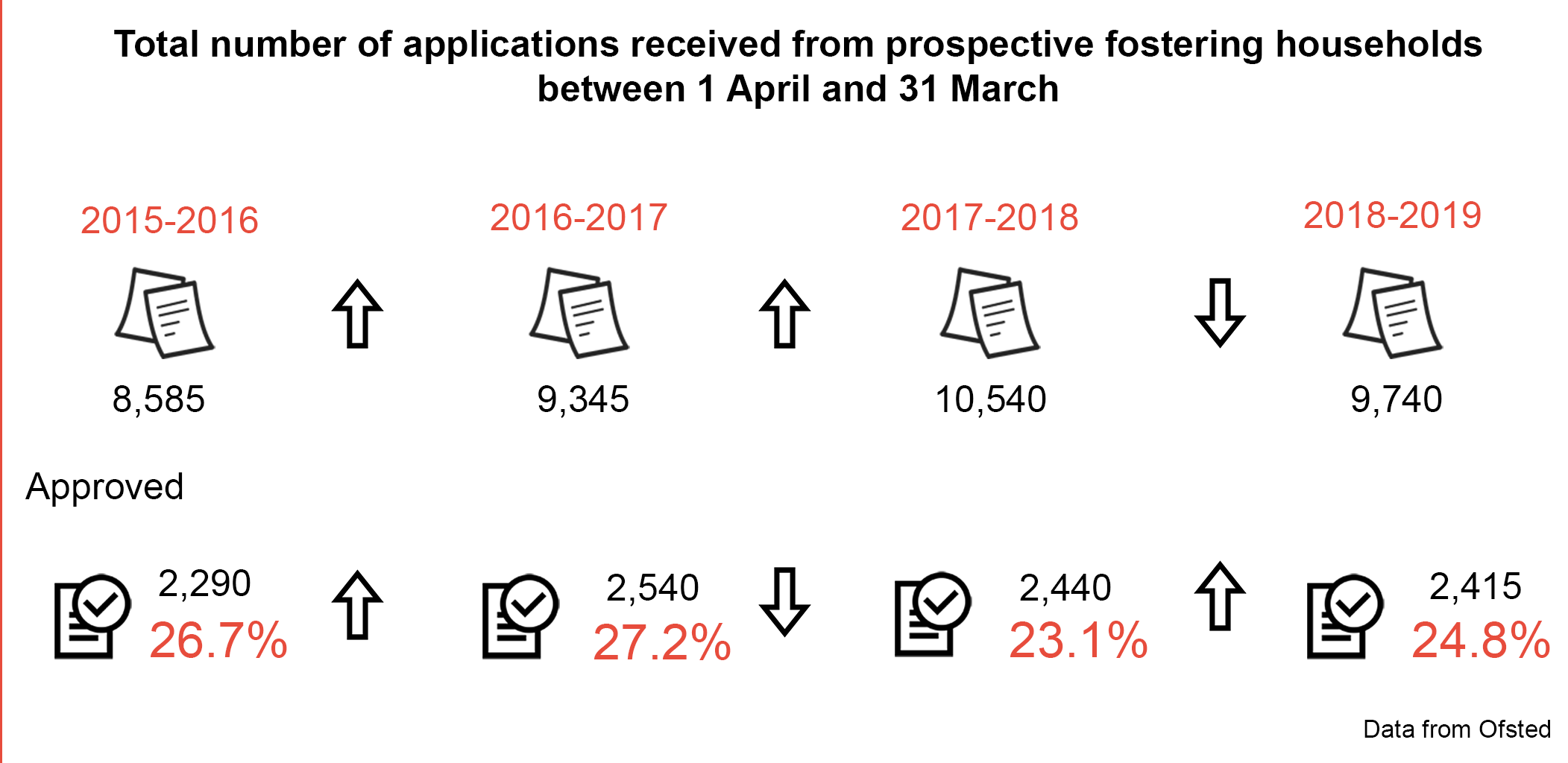

Another factor that shows there is a crisis is the number of applications from prospective fostering households.

The number of applications is increasing, but fewer applications are now approved.

The number of applications is increasing, but fewer applications are now approved.

The number has increased slightly overall in the past three years, from 8,585 applications to 9,740. This means more people are choosing to foster.

However, only a quarter of the applications were successfully approved in 2018-2019, meaning the remaining were either withdrawn or rejected.

The number of applications approved has decreased slightly from 2015, by approximately two percentage points over the four years.

"Approving applications requires a lot of time because there are several things to check, from criminal records to professional training," Williams says. "Even if there is going to be a larger volume of applications, that doesn't mean we are going to end up with more foster carers at the end of the year.".

"It is also about the quality of the applicants. It's like applying for a leading company."

The requirements and checks to become a foster carer are stricter now than in the past. This is to avoid employing foster carers who are doing the job for money and could potentially cause the children harm.

So, what does it really take to become a foster parent?

Source: The Fostering Network via YouTube

![[object Object]](./assets/3koyX0rI2H/fostercarersneeded-1890x1417.png)

Ann is a former foster carer. In 21 years of fostering, she welcomed 18 children under her roof. Despite having two children of her own, she adopted one of the children she was looking after. In 2018, Ann reached a turning point. Due to a lack of support from the local authorities, Ann stopped fostering. She opened a business to support women who’ve been subjected to domestic abuse.

Ann encourages me to take a seat by the wooden table in her dining room. She reaches one of the highest shelves in the room and takes what, at first sight, looks like a jam jar full of notes.

She sits in front of me and grabs a small piece of paper. “When am I going home?” she reads. “What happened to mum?” says the next.

Ann reveals the purpose of the jar: to make her placements feel safe.

“You never know what is coming through the door, but all children have something in common: they want answers. I want to let them know this house is a safe place where doubts are cleared up.”

Ann would find up to 10 questions inside the jar each morning.

“As soon as I had the opportunity, I would take time to answer those questions," she says. "I used to do it in a very natural way as we were having a conversation about how the day went.”

Ann's first experience as a foster parent was daunting; she already had two children of her own and, at the beginning, she had to make adjustments to her house.

“I had two bedrooms where my kids were sleeping separately,” she says. “But when my first placement came in, they started to share the same room because each placement is required to have their own bedroom.”

Ann's family gave up communal spaces and her children had to share their mother's attention with the placements. Nevertheless, both Ann and her two sons developed a strong attachment to each foster child.

“When they leave is the hardest thing,” she says. “I’ll never get used to that feeling of grief I had every time a placement was leaving. After all, I’ve been their mum.”

Ann had mostly been a short-term carer, with children spending between one week to six months under her wing. It was only in 2010 when Ann adopted Kevin, one of her placements, that she became a permanent foster carer.

“I had to teach my own children how to detach quickly from a placement," she says. "At the same time, they had to learn how to create a strong bond between siblings.”

Most of Ann's placements stay in contact with her and her sons, which is one of the most rewarding things about fostering.

“Most of the children I fostered are now finishing university and some of them have children on their own which makes me a grandmother. They send me cards with pictures, but they mostly stay in contact with my sons via social media. We are like a very big family.”

But in 2018, Ann stopped fostering.

“I didn’t feel safe,” she says. “I didn’t feel supported. It got to the stage where it was affecting my children.”

Ann blames the current fostering system; social workers and local fostering services lack understanding.

“They don’t live with the placements, they probably see them three or four times,” she says. “I had children with special needs, and I had to go out there and pay for extra-care and support because social workers wouldn’t realise how hard it’s to cope by yourself.”

With the current system, where foster carers are not allowed to set specific preferences for their placements, it’s crucial to be able to rely on the authorities.

“Fostering can be very rewarding, it’s about saving people’s lives,” she says. “But the amount of challenges we face because of the lack of support often discourages people to continue fostering.

"If social workers were more present and the fostering authorities would get more involved in the day-to-day life of the children, we’d no longer hear of a foster care crisis.”

Listen to Ann's experience in this four-minute interview.

Ann had been a foster carer for 18 years before she decided to abandon the profession. Source: Andrae Ricketts

Ann had been a foster carer for 18 years before she decided to abandon the profession. Source: Andrae Ricketts

Ann uses this question jar where the foster children can ask any question that comes to mind. This method builds trust with them. Source: Giulia Basana

Ann uses this question jar where the foster children can ask any question that comes to mind. This method builds trust with them. Source: Giulia Basana

Explaining the crisis

Monique Butler, social worker

Monique Butler is a social worker who specialises in leaving care. These are young people between the ages of 18 and 25 who’ve reached adulthood but have decided to keep living with their foster parents. Every day, Monique meets up with these young adults for one-to-one discussions about their care home conditions.

Monique believes the current social care system is unsuccessful because there’s not enough intervention when problems emerge in the person’s birth family.

“You need to address things at the start, not once the children are in care,” she says. “We need to establish support services in the broken families, so a child doesn’t go through trauma in the first place.”

The lack of support from social workers to help foster carers has meant there’s not enough social workers in the system either.

"We have to talk about a social worker crisis," she says. "We have so many responsibilities and very little support. It's a domino effect."

A decrease in foster carers in recent decades is caused by economic and societal pressure that foster parents are continuously exposed to.

“Most of these young people come from traumatic backgrounds and so they don’t know how to function in a normal household. This makes foster carers feel at risk and unprotected. Not many people are eager to risk their own family to save the life of a stranger.”

In the past, adoption was the privilege of a few. Children who were abandoned by their birth-family were likely to end up in orphanages and workhouses.

“During the 1950s and 1960s, the UK saw an economic boom,” she says. “The number of foster parents increased because the government had more money and could offer at least economic support to foster carers, who made fostering their primary income.”

Now, the situation is different - fostering isn’t worth the money.

“Every foster parent must be driven by a bigger sense of community and love,” Monique says. “Otherwise you wouldn’t even explain why there are still foster carers around.”

Social workers are trying to primarily act in spotting abusive households, removing children at risk and placing them into care quickly.

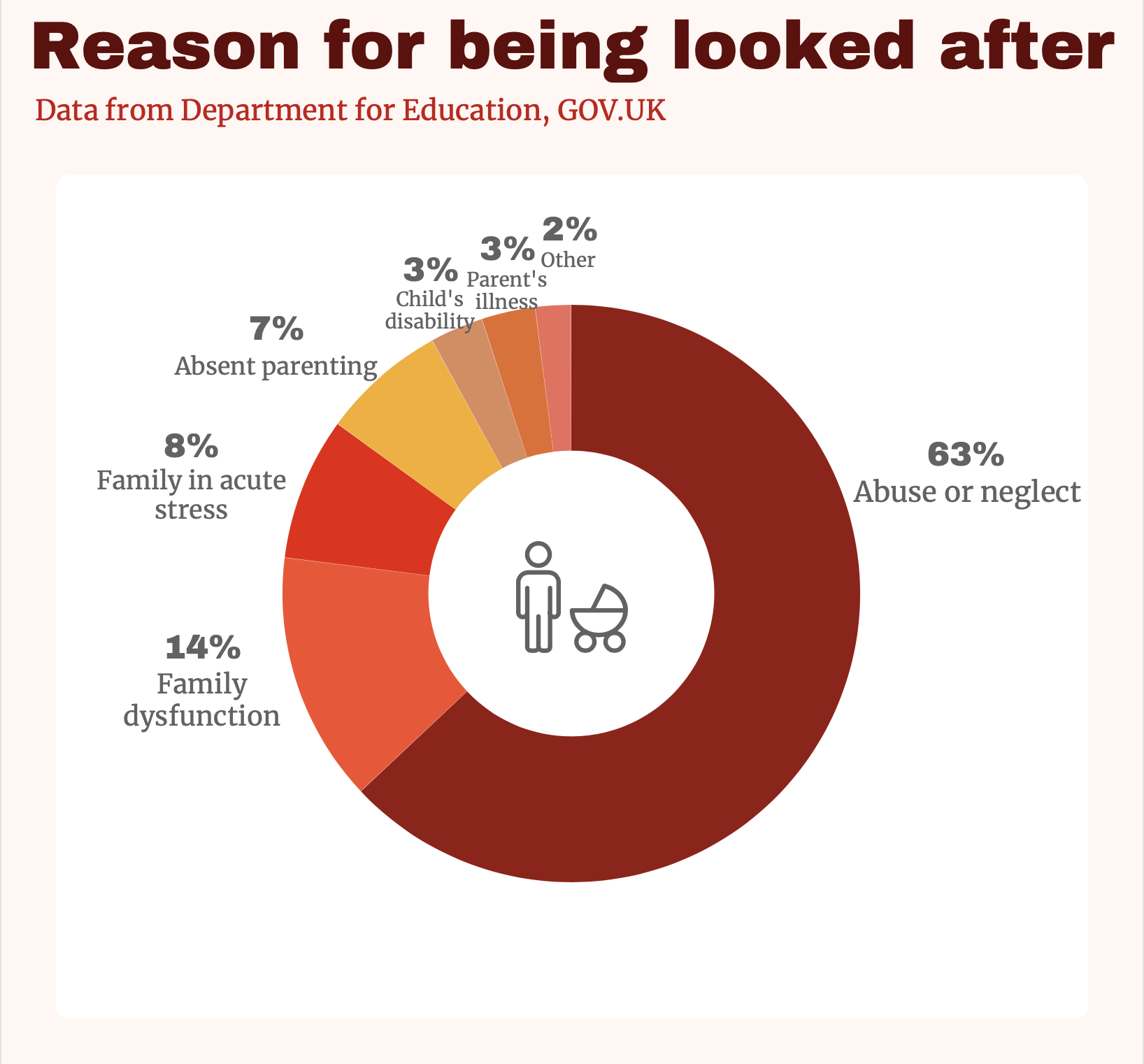

Most children who end up in the care system are the victims of neglect by their birth-family, with almost half of them have been emotionally or physically abused.

However, this isn’t the only motive. Two in five children are placed in care because of other reasons, including family dysfunction and a disability.

“We need to focus more on these other cases,” Monique says. “Although some of them, such as absent parenting and family stress, fall into abuse and neglect, reasons like a child’s disability must be equally considered.”

Monique suggests more money should be invested for therapy or treatments. Family interventions and more awareness of the support available could all be solutions to tackle the fostering crisis.

“Prevention is better than cure,” she says. “We must solve the problem at its roots.

“As young individuals, we are taught compassion and kindness. Hopefully young generations will be inspired to become foster carers in the future, although this isn’t a certain solution.”

For now, Monique is doing what she can to support young people in care and inspire future generations. Watch the video for more.

Could millennials be the solution to the foster care crisis?

Amelia Durkin, care leaver

Millennials are a special generation. Like all generations, they grew up playing outside with friends, but uniquely they also witnessed the technological boom as it happened. For this reason, generally, possess qualities that would naturally be beneficial to fostering children.

However, only three percent of foster carers are under the age of 30.

Millennials are known for their desire to make changes in society. According to research by Capstone, people born between 1981 and 1996 have stronger work and family values and a bigger sense of acceptance. These are excellent qualities for fostering.

Furthermore, millennials tend to be more flexible than previous generations which is fundamental when having to balance a child’s need and a job.

However, there’s disagreement about why there’s such a lack of foster carers in their 30s.

Amelia Durkin, who’s experienced being in foster care, thinks she might know why.

Amelia has been in care with her grandparents since the age of eight. Her mum wasn’t able to look after her because of a serious mental health issue that social workers failed to identify.

“I’ve been lucky my grandparents were happy to take me under their wing,” she says.

"Although I wish the social services were able to spot the illness before classifying her as a danger for me and my brother.”

From the left: Amelia, her little brother, her grandparents and her cousin. Source: Amelia Durkin

From the left: Amelia, her little brother, her grandparents and her cousin. Source: Amelia Durkin

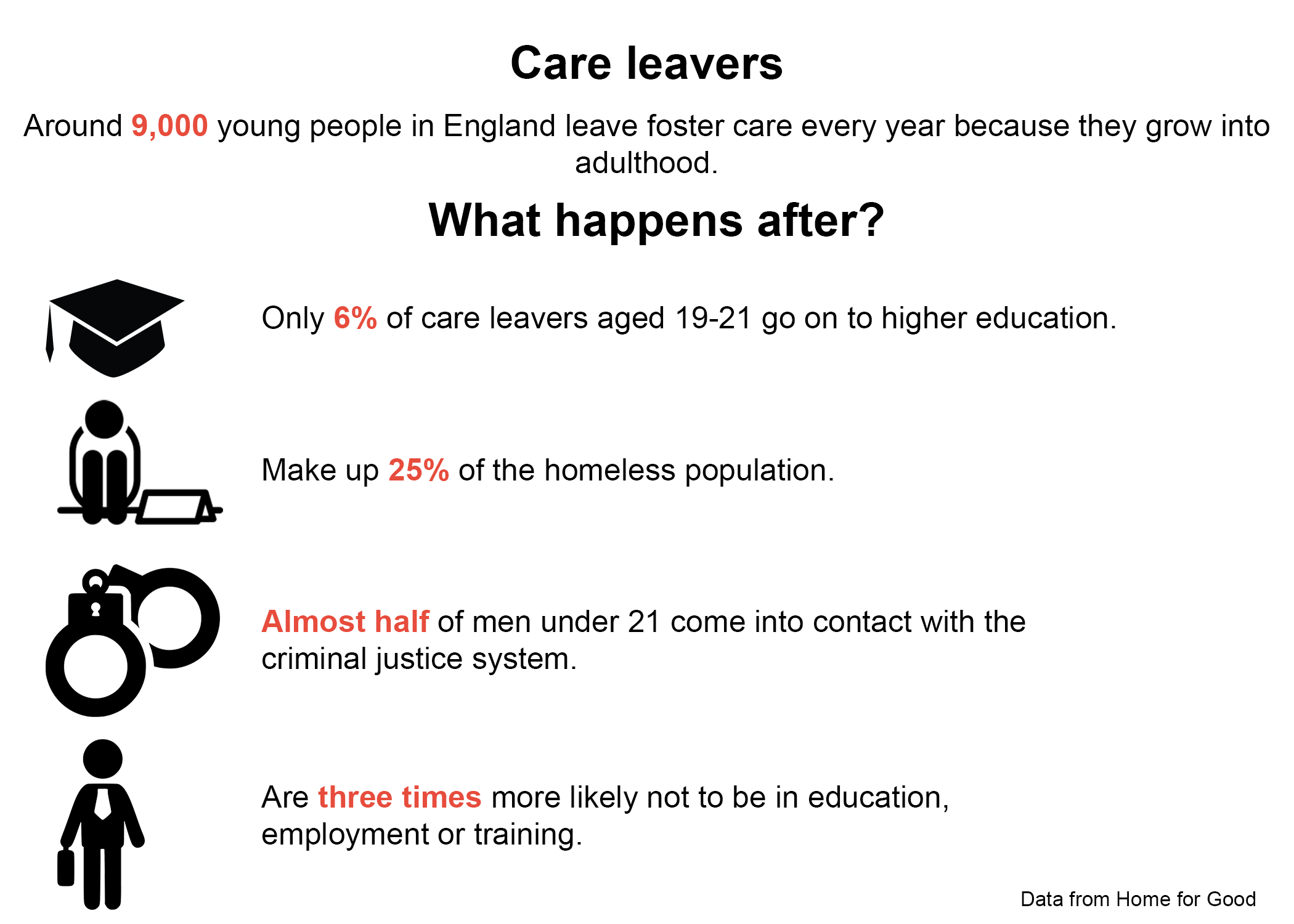

Although Amelia’s experience hasn’t been like most care leavers, only eight percent of them are looked after by family or friends, in reality it was no different.

“I used to visit my grandparents quite often even before being placed in care with them,” she says. “But I still had to go through all the legal procedures, including meeting up with social workers.”

Amelia says social workers weren’t supportive during her childhood and were an additional stress.

“I had eight social workers in 13 years,” Amelia says. “I didn’t have time to bond with any of them because they kept changing and it was very frustrating.”

Amelia grew up with a lot of societal pressure due to her condition.

“There's this stigma around care leavers that most of us will end up in prison or unemployed. Well, I didn’t want to be part of that group.”

Despite suffering from Type 1 diabetes, Amelia has never given up on her dream goal. She’s now about to complete her undergraduate degree in Law and has already secured a solicitor training contract.

“If it wasn’t for my foster carers, I don’t think I would have survived. I am infinitely grateful.”

Once Amelia is financially stable, she’ll definitely consider fostering.

“You need time and total dedication when you decide to become a foster carer,” she says. “Most millennials have now just started their career and it’ll be years before they are financially stable and settled.”

Another reason why millennials may not be able to foster is because most of them don’t own a property.

“Having a stable home was fundamental to me as a child,” Amelia says. “But unfortunately, home prices constantly increase so we either live with our parents or rent for most of our life. It isn’t the best environment to raise a child.”

Although millennials would make the perfect candidates with their energy and solid values, today’s society makes fostering a difficult profession to pursue for youngsters.

“We might need to wait a few years,” Amelia says. “But millennials will eventually reach an age when they’ll feel comfortable to foster. And I’m sure, when this time comes, there’ll be millions of people stepping forward. I’ll be one of them.”

A 22-year-old foster carer shows a typical day in her fostering life, including good moments and her struggling. Source: Precious Star Vlogs, Youtube

While fostering can be an extremely rewarding and successful profession which helps save the lives of many people in need, often the struggles of such a crucial role outweigh the benefits.

A solution that solves the crisis is still a long way off. In order to recruit more foster carers, the relationship between fosterers and local authorities needs to be tightened, the system must receive more funding and foster carers need to show more flexibility when it comes to looking after a child with special needs.

I spoke to many foster carers not mentioned in this project and other care leavers who have shared their stories. I found these people driven by love and gratitude, despite the economic hardship and mental/physical challenges both sides had faced. Unfortunately, fostering doesn’t receive the media coverage it deserves. For this reason, especially during this time of crisis, I hope I’ve shed light on a complicated issue and inspired some readers to consider fostering themselves. - Giulia Basana