TRAPPED AND TARGETED: THE UNFAIR POLICING OF YOUNG ETHNIC MINORITIES IN LONDON

Trigger warnings: Physical violence, abuse, suicide, death

Decades of tension

On 22 April, 27 years ago, the murder of 17-year-old Stephen Lawrence at the hands of a white gang left such a deep scar on the nation, that the day was made in remembrance of him.

Lawrence was an ordinary teenager who was waiting in a bus stop in Eltham, south-east London, when he was stabbed to death unprovoked.

After the racially-motivated murder case was tossed aside, it was found that there was institutional racism within the police force.

Almost three decades later, activists from BAME communities in London are still pleading for change in unfair policing treatments towards ethnic minorities.

THE REALITY OF BEING BLACK IN LONDON

Last October, Jesse Bernard was walking to his father’s house in east London, when he was followed and stopped by a police car. As a 30-year-old black man who grew up in Hackney, this is something he is already used to.

“When I was younger, there were cases where I was just out with my friends in the park,” he says. "The police would come up to us to say there’s been reports of a robbery in the area, and that we 'fit the description’. They would pat us down, and sometimes would pass handcuffs — which wasn't allowed, because we weren’t being detained. We were kids.”

Photo credit: Jesse Bernard

Photo credit: Jesse Bernard

The latest Home Office report from 2017/2018 shows that black people are still ten times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people in England and Wales. This trend has remained the same over the past decade.

THE HISTORY OF RACIST STREET POLICING

In April 1981, Brixton, London and other major cities in England saw an uprising from black communities, in response to what was known as the sus (stop and arrest) laws, which disproportionally targeted black people.

The sus law was repealed in the same year, but modern stop and search is still believed by some to be fundamentally racist.

This is how they targeted and implemented stop and search on black youths in London now we all getting a taste of it first hand

— Sha (@ShanqiueB) April 13, 2020

CEO of social justice charity Voyage Youth Paul Anderson was 15 when he participated in the Brixton riots, and he recalls a video documentary he made during the event.

"In that documentary, I was protesting about the ‘sus' laws, police brutality, disproportionality — all of which are still happening now," he says, in distant remembrance. "The saddest thing for me is that BAME communities are having the same conversations now, as we were 40 years ago."

Dr. Alexandra Cox, a senior criminology lecturer at Essex University, says that the current stop and search trend reflects the lack of progress that the Met has made in addressing ethnic disproportionality in the criminal justice system.

DISPROPORTIONAL STOP AND SEARCH - JUST THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG

In 2017, MP David Lammy conducted an independent inquiry into the treatment of ethnic minorities in the criminal justice system, which was commissioned by Prime Ministers David Cameron and Theresa May.

According to the review, if you're black, you're 53% more likely to end up in prison. If you're Asian, the number is 55% and if you're of other ethnic groups, it's 8%.

Black men were also 26% more likely to be remanded in custody than white men, and 40% of young people in custody are from BAME backgrounds. The economic cost resulting from BAME overrepresentation is £309 million a year.

In 2015, anti-racist think tank the Institute of Race Relations reported that a disproportionate amount of young ethnic minorities die in custody, due to neglect or use of force.

From 1991 to 2014, there were 137 recorded BAME deaths in police custody under suspicious circumstances. Out of the 137 deaths, 78 were black, and 31 were Asian. 61% took place in London. Some cases show that disproportionate levels of force were used towards prisoners who were racially stereotyped as violent.

"Racism has barely changed"

Photo: Y-stop application screenshot, originally sourced by Kezia Kho

Photo: Y-stop application screenshot, originally sourced by Kezia Kho

Like Anderson, Bernard also feels police racism has barely changed since his teen years in the 1990s.

Experiencing it first-hand is why Bernard now works with the stop and search Y-stop, a mobile application which can help young people on what to do in case of a stop and search.

Bernard breaks down what to do during a stop and search. On Y-stop, users are able to read more on stop and search rights, record an unwanted incident, or complain to authorities.

A tool such as Y-stop is much needed because like him, "a lot of kids don’t know their rights, and would get stopped because of their skin colour", says the project leader.

From his perspective, it isn’t all that difficult to explain why discriminative policing still exists. “If you look at it historically, the police was created to protect the rich and white," he says. "They weren’t interested in protecting the poor or the minorities."

He feels this piece of history trickles down to modern policing, where perhaps what's mainly changed is that "the police are more sophisticated in their tactics”.

“Kids are no longer being beat up in the back of the van or in dark alleyways anymore. But there are still cases of abuse of police powers that got exposed.” - Jesse Bernard, journalist and spokesperson for stop and search project Y-stop

Just yesterday, a video circulated of a black man being tased by a police member in front of a crying toddler in Manchester. Details behind the incident haven't emerged, and the Manchester Police hasn't responded. TW: Physical violence

This just happened a few hours ago @gmpolice pic.twitter.com/0sIwn3NrHI

— Yaa🇬🇭 (@essmurph) May 7, 2020

Last July, an officer was caught striking and pinning down an Arab man having seizure in Tower Hamlets, east London.

A recent non-ethnicity related case sparked outrage after a Lancashire officer was caught yelling to a white man: "I'll lock you up. I'll make something up. I'm a police officer. Who are they going to believe, me or you?"

"I'll make something up." https://t.co/1PVlswXTfN

— Aaqib Javed (@Aaqib__Javed) April 18, 2020

The incident is now under investigation by the Lancashire Police.

What needs to be done?

“Officers need to be reminded to adhere to fair practices and protocols." - Paul Anderson, CEO of BAME charity Voyage Youth

Dr. Cox says that to improve their relationship with the community, the police as an institution, has to acknowledge their record of abuse.

“The history of over-policing of black communities, or prominent deaths of people in custody, are remembered by generations of people, who think of the police almost as a colonial presence," she says. “You learn from your grandfather about how the police were a negative force. That knowledge is passed on generationally.”

Anderson, whose decades of activism has heavily involved working with the police, feels that there isn’t adequate training in police stations about how to address their history of racism.

“When I go to police stations, I don’t see any evidence of how effects of stop and search have been written in large for every officer to see," says the activist. "Officers need to be reminded to adhere to fair practices and protocols, and their impact on communities."

Another hinderance is their superficial engagement with the community, notes Dr. Cox. “Often times, consultations with communities happen in a very surface level way, like community boards or gatherings," she says. "But ultimately, those consultations are ignored."

The Metropolitan Police and other policing groups have declined to offer their comments.

Looking further:

What is perpetuating the criminalisation of ethnic minorities?

"Systematic failure and state abandonment"

While a large number of BAME people are unfairly targeted for policing, the number of BAME youth committing crime is still a major concern.

According to the Lammy review, half of all knife crime offenders and victims in London were BAME. Within all BAME offenders, half were under 25.

But this statistic should be treated as a reflection of various systematic failures, says Dr. Cox, who views that this could only change through systematic changes, starting from education.

In 2012, the Ministry of Justice found that 63% of prisoners reported being temporarily excluded when at school.

Zahra Bei, founder of grassroots coalition movement No More Exclusions calls to action a stop in the disproportional exclusion of black students from schools - something she witnessed while teaching in a Pupil Referral Unit back in 2011.

“I thought when I first started working in a Pupil Referral Unit, that I was doing something good," she says. "I then realised that I was colluding with a segregationist education system which excludes and alienates."

“What the prison is to me, is similar to what a Pupil Referral Unit is. It’s somewhere to deposit people who have a whole range of issues in their lives which society has failed to support them with." - Zahra Bei, founder of grassroots movement No More Exclusions

Bei observed how black students as young as 5 were excluded and punished much more harshly compared to their peers.

These unfair treatments existed in a lot of forms, ranging from suspension to isolation units.

"A child might not be permanently kicked out of school, but they might be placed in an isolation unit for four hours, days, or weeks at a time," she says. "We've heard stories of children becoming suicidal from it."

Bei, who has had more than a decade of experience as a schoolteacher, explains the effects of school exclusion on children.

“The criminalisation of young black and Asian men in England and Wales is terrible. They are deemed as more violent, more unruly, and less receptive to treatment in the community, while not factoring in how the system is failing them.” - Dr. Alexandra Cox, senior criminology lecturer at Essex University

According to the anti-exclusion coalition founder, the effects of school exclusion are compounded when paired with challenging economic backgrounds, lack of parental support and other special needs. These conditions may then push children into the cycle of youth violence.

Crime Domain of LSOAs (neighbourhoods) in London. Source: Indices of Deprivation 2019

Crime Domain of LSOAs (neighbourhoods) in London. Source: Indices of Deprivation 2019

Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index of LSOAs (neighbourhoods) in London. Source: Indices of Deprivation 2019

Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index of LSOAs (neighbourhoods) in London. Source: Indices of Deprivation 2019

Back-to-back comparison of the most concentrated areas for crime and the most concentrated areas for income deprivation affecting children in London shows that they overlap. Source: London Assembly

Having been a panel advisor for youth offenders, Dr. Cox says that the cases she has worked on are "mostly second generation immigrant kids, who have been provided with few academic and financial resources, whose families have also experienced systemic neglect".

“Every single kid whose panel I've worked on has not been in school for two years, or they've been in a Pupil Referral Unit, and no one has asked why," says the criminologist. "I've been shocked to see that the main focus in panels has been on their character, as opposed the ways that the systems that they were in may have failed them. When I look at this, I think of it as state abandonment.”

Dr. Cox on youth violence and how it "reflects conditions of living in a violent state".

“We need to give young people hope"

Anderson says that conditions such as lack of opportunity, lack of role models and the lack of hope for a better life create a harrowing reality for a lot of BAME kids.

He says: “There is a fatalistic attitude which is: ‘I didn't do well in school, and got in trouble here and there, so I don't have anything at stake.’"

"It's almost a self-fulfilling prophecy," says Bei. "When people don't have hope, they act like they got nothing to lose. They act out. They start to say, 'This is how society expects me to be'.'"

The No More Exclusions founder feels that a solution to tackle the complex issue of systematic racism starts with more compassion from society towards young minorities, especially factoring in the conditions they grow up in.

One of the ways Anderson's charity Voyage Youth is working to tackle the cycle of youth crime, is by educating youngsters about the conditions around them, so they don't fall victim to them.

“We tell them, ‘There's a bed waiting for you in prison. They're waiting for you to do something wrong.' Our job is to then get into their psyche and give them hope. We keep telling them that they can do better than what society, the police and the media are expecting of them."

For more information on fair policing, visit http://www.stop-watch.org/

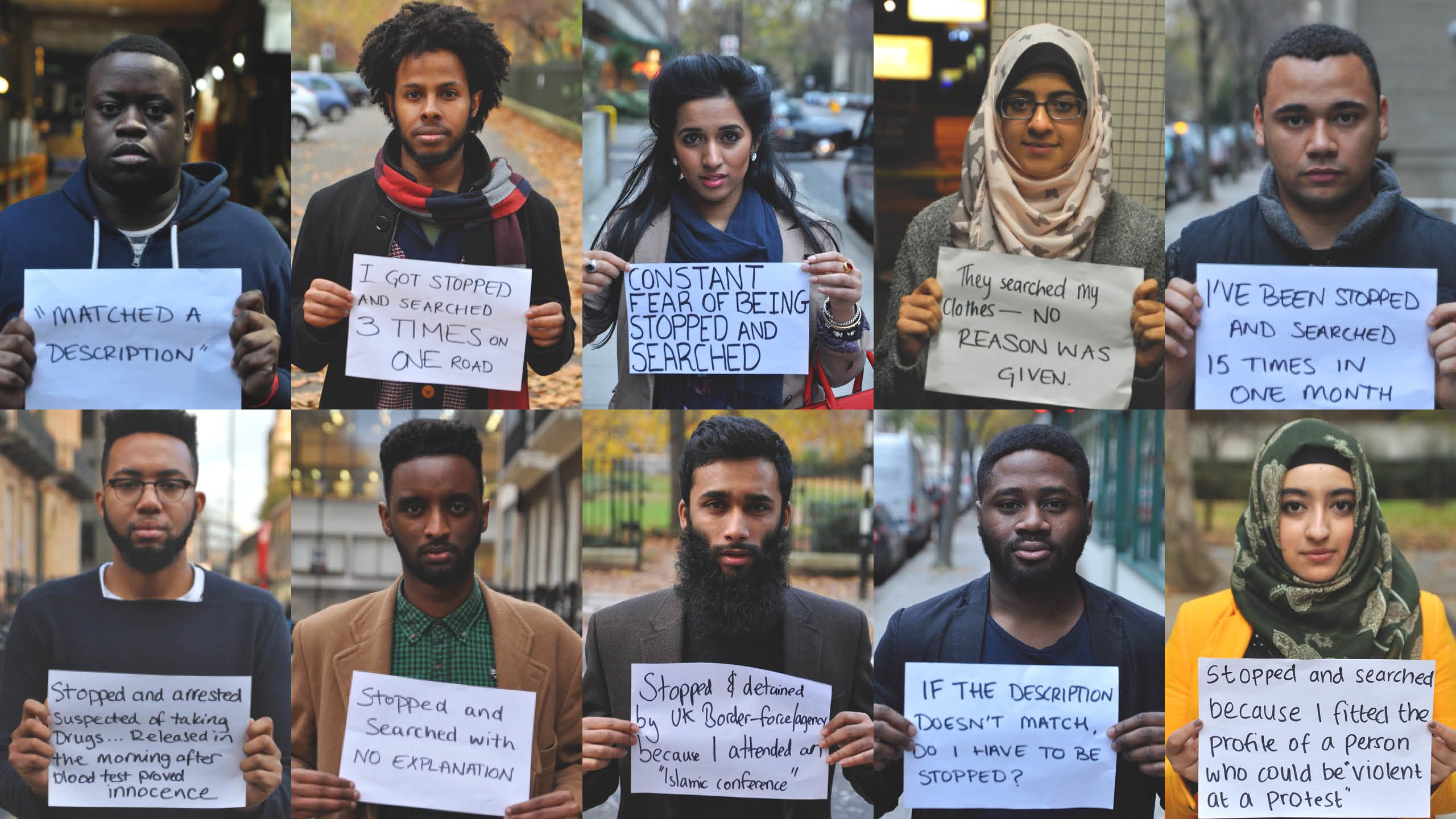

Cover image: These photos are a collage of Darren Johnson's stop and search project with UK students.

Original source: EYE DJ on Flickr

The rest of the image credits (in order of appearance):

3. mwangi gatheca on Unsplash

4. Kai Pilger on Unsplash

5. Markus Spiske on Unsplash

6. Toa Heftiba on Unsplash

Special thanks to Jesse Bernard from Release UK, Paul Anderson from Voyage Youth, Dr. Alexandra Cox from Essex University and Zahra Bei from No More Exclusions